“Better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer”

William Blackstone Commentaries on the Laws of England (vol 4) 358

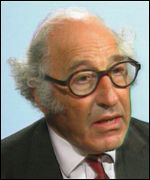

With very little coverage (Day 1: Irish Times here and here | RTÉ; Day 2: Irish Times), a case which had the capacity to make a fundamental change to Irish defamation law was decided in the Supreme Court at the end of last week. Two members of the Birmingham Six have taken defamation proceedings against leading English human rights barrister Sir Louis Blom–Cooper QC (pictured left). Blom-Cooper sought to have the case struck out on the basis that his expression of opinion was constitutionally protected. However, the Supreme Court allowed the case to proceed, and (if the press reports are accurate) ducked the constitutional question, at least for the time being.

With very little coverage (Day 1: Irish Times here and here | RTÉ; Day 2: Irish Times), a case which had the capacity to make a fundamental change to Irish defamation law was decided in the Supreme Court at the end of last week. Two members of the Birmingham Six have taken defamation proceedings against leading English human rights barrister Sir Louis Blom–Cooper QC (pictured left). Blom-Cooper sought to have the case struck out on the basis that his expression of opinion was constitutionally protected. However, the Supreme Court allowed the case to proceed, and (if the press reports are accurate) ducked the constitutional question, at least for the time being.

The story begins with the presumption of innocence, embodied in the quote from Blackstone, above. In Woolmington v DPP [1935] AC 462, [1935] UKHL 1 (23 May 1935) Viscount Sankey held that “the presumption of innocence in a criminal case is strong”, and emphasised, that throughout the web of the criminal law,

… one golden thread is always to be seen that it is the duty of the prosecution to prove the prisoner’s guilt … If, at the end of and on the whole of the case, there is a reasonable doubt, created by the evidence given by either the prosecution or the prisoner, as to whether the prisoner killed the deceased with a malicious intention, the prosecution has not made out the case and the prisoner is entitled to an acquittal. No matter what the charge or where the trial, the principle that the prosecution must prove the guilt of the prisoner is part of the common law … and no attempt to whittle it down can be entertained.

Furthermore, it is now clear that the presumption of innocence does not merely apply during the course of a trial. In R v Hickey [1997] EWCA Crim 2028 (30 July 1997) the Court of Appeal in England held that, where an appeal court quashes convictions, the presumption of innocence in respect the appellant is re-established. In J O’C v DPP [2000] IESC 58 (19 May 2000), Hardiman J referred to Hickey and other cases to conclude that

… the presumption of innocence applies to all unconvicted persons. This is so whether they are unconvicted because the trial has not yet taken place or because a conviction has been quashed.

The whole issue is brilliantly treated in Claire Hamilton‘s superb book The Presumption of Innocence in Irish Criminal Law. ‘Whittling the Golden Thread’ (Irish Academic Press, Dublin, 2007). However, at least in the context of convictions set aside on appeal, this was not an incontestable view of the law. In 1997, Blom-Cooper, argued that the Court of Appeal got it wrong in the Hickey case, and that the presumption of innocence persists until a conviction, but once it is gone, it is not revived by the quashing of the conviction on appeal.

Commentators disagree with judges all the time. Indeed, I have done so regularly on this blog. And Blom-Cooper is an outspoken commentator who regularly argues for alternative views of the law. However, in this case, he may have gone too far. He made this argument in a pamphlet called The Birmingham Six and Other Cases. Victims of Circumstances (Duckworth, 1997). In it, he examined recent miscarriages of justice, such as the case of the Birmingham Six (pictured right), to raise once again his longstanding objections to the current system of trial by jury and to explore the consequences of the professional failure to explain the function of the Court of Appeal. Two of the Birmingham Six, Gerry Hunter and Hugh Callaghan, sued Blom-Cooper and his publisher, Duckworth, for defamation, alleging that various comments made by Blom-Cooper in the pamphlet constituted both an overt and a covert attack upon their innocence.

Commentators disagree with judges all the time. Indeed, I have done so regularly on this blog. And Blom-Cooper is an outspoken commentator who regularly argues for alternative views of the law. However, in this case, he may have gone too far. He made this argument in a pamphlet called The Birmingham Six and Other Cases. Victims of Circumstances (Duckworth, 1997). In it, he examined recent miscarriages of justice, such as the case of the Birmingham Six (pictured right), to raise once again his longstanding objections to the current system of trial by jury and to explore the consequences of the professional failure to explain the function of the Court of Appeal. Two of the Birmingham Six, Gerry Hunter and Hugh Callaghan, sued Blom-Cooper and his publisher, Duckworth, for defamation, alleging that various comments made by Blom-Cooper in the pamphlet constituted both an overt and a covert attack upon their innocence.

Once the Irish High Court had held that the case could be brought in Dublin, Blom-Cooper sought to have the case struck out on the basis that he had done no more than to express an opinion, which was a right absolutely protected by the Irish Constitution. It was an extraordinary claim – the right to freedom of expression protected by Article 40.6.1(i) of the Irish Constitution is still under-developed, and was considerably more anaemic ten years ago – but the argument held out the prospect of improving this state of affairs. In the High Court, his counsel, Michael Ashe QC, argued that the essential issue in the case was

… whether the constitutional guarantee to express freely convictions and opinions prevails over the constitutional protection afforded to one’s good name. … [He] submitted that the defendant is entitled to express freely his convictions and opinions as appear in the booklet, … [and] that what is at issue is the balance between Article 40.6.1 and 40.3.1 of the Constitution and Article 40.3.2. of the Constitution. The question posed is whether and to what extent the common law of defamation, which has been developed over centuries, reflects and implements an appropriate constitutional balance. … [He submitted that the plaintiffs’ defamation action] represents a disproportionate interference with the right of freedom of expression … [and] that the right of the defendant to express freely his convictions and opinions about matters of importance is fundamental in a democratic society … [He contended] that the booklet represents such an expression on matters which are public property and further the booklet represents legal analysis and comment. Having regard to the provisions of Article 40.3.2 of the Constitution, … [he] submitted that while an attack on the character is possible the Constitution is concerned with unjust attack … [and] that the instant actions represent a disproportionate interference with the freedom of expression which pre-dominates as a constitutional right. …

[He argued that] the freedom to advocate an idea is a core guarantee of Articles 40.6.1. and 40.3.1. of the Constitution, … that the political function of free speech is of paramount importance in our constitutional democracy, … that the freedom of expression recognised by the Constitution must not be inhibited by a deterrent factor of the law of defamation and that if the inhibition goes too far it may undermine the constitutional right to freedom of expression, … [and] that the freedom of expression involving the advancement of knowledge in the ‘market place of ideas’ is essential in a democratic society.

The scope of this submission was breath-taking, and it was supported by reference to caselaw from the US Supreme Court, the European Court of Human Rights, and courts of final appeal in the UK, Australia and New Zealand. In Hunter v Duckworth [2003] IEHC 81 (31 July 2003), Ó Caoimh J made many comments about the importance of the constitution’s protections of freedom of expression, and how they must be balanced against its concomitant protections of the right to good name, and he concluded that the former right should not be viewed as paramount to the latter, and he concluded that

… I must rule against the defendant on the issue insofar as the same was formulated. Nevertheless, I am satisfied that the defendant has raised issues of particular importance on the trial of this issue, which have not been fully addressed previously. However, I believe that the issues raised on the trial of the issue before me are such that the defendant should be permitted to amend his defence in light of the ruling of this Court, with liberty to the plaintiff to plead to any such amended defence. I will hear counsel in relation to any time that may be required for such amended pleading.

In other words, the Blom-Cooper lost on his claim that he had an absolute constitutional right or privilege to express his opinions. He appealed this issue to the Supreme Court; and – last Thursday – the Court dismissed the appeal, seemingly on the grounds that the constitutional issue could not arise until the facts of the case had been fully established. I will return to this if there is a written transcript of the decision.

Given this conclusion, however, it means that other elements of Ó Caoimh J’s decision do not seem to have been considered. For example, to sweeten the pill for Blom-Cooper – in an aspect of his judgment which continues to confuse me – Ó Caoimh J held that, since he had considered important constitutional issues, Blom-Cooper could amend his pleadings to take account of the judgment. I remember that, at the time, this was regarded as either a score draw or even a moral victory for Blom-Cooper. However, it was unclear to me then, and is still unclear to me now, exactly how Blom-Cooper might take advantage of Ó Caoimh J’s concession. The essence of Micheal Ashe QC’s submission was that the common law should be refashioned in the light of constitutional norms; and Ó Caoimh J accepted that this would be so, but only if a conventional interpretation of the law of defamation did not satisfy the requirements of the Constitution. Ashe had relied on cases relating to qualified privilege in the US and elsewhere in the common law world to demonstrate how the law of defamation could be moulded to conform with constitutional principle, and to argue that they should be applied by analogy to support the different but parallel contention that the common law relating to opinion (rather than privilege) was inconsistent with the constitution. Bizarrely, Ó Caoimh J spent most of his judgment examining the substantive development of the law relating to qualified privilege, and even held that one of them – the decision of the House of Lords in Reynolds v Times Newspapers [2001] 2 AC 127, [1999] UKHL 45 (28 October 1999) – was the most appropriate way of approaching the problems in the case before him. On the issue of qualified privilege, the High Court later came to a similar conclusion in a case in which the issue had properly arisen.

However, a flexible approach to qualified privilege would have availed Blom-Cooper not one jot, as he was seeking to rely upon a different principle. Of course, it may be that what Ó Caoimh J was approving was what he characterised as “the flexible approach represented by that decision” rather than the detail relating to qualified privilege. Moreover, he did acknowledge that,

insofar as the publication at issue in these proceedings largely comprises expressions of opinion, it appears that these can be addressed under the law as to fair comment, but that that law should be construed liberally to afford a proportionate right to freedom of expression of opinion, even when such expressions may give offence.

So, it may be that he did appreciate that the constitutional reformulation of the common law in the qualified privilege cases was being relied upon by analogy, so that the flexible approach in those cases should be analogically applied to the context of fair comment. If so, then the revision of the pleadings which he was prepared to countenance was to accommodate this liberal defence of fair comment. Because Ashe had made the extreme argument that the plaintiffs’ claim necessarily failed simply because the pamphlet represented Blom-Cooper’s opinion, the rather less far-reaching point that the common law on fair comment might be re-evaluated in the light of the constitution was not pursued. This is a pity. But it may nevertheless still arise. Presumably, Ó Caoimh J’s concession of that the pleadings can be amended still applies. If so, then this is what Ashe should do on Blom-Cooper’s behalf. And if he does, then a further appeal to the Supreme Court may very well determine the extent of the impact which the constitution has upon the law of defamation. However, the Supreme Court’s dismissal of last week’s appeal on very narrow grounds means that neither Ashe’s very broad submission, nor Ó Caoimh J’s narrower concession, was addressed. The Court ducked these constitutional questions, and therefore did not make any change at all, let alone a fundamental one, to Irish defamation law.

The constitution of India says:

let hundred guilty persons be acquitted but one innocent person should not be convicted

Hi there,

Thanks for the comment. I’m not sure it’s right, though. I can’t find anything like it in the Indian Constitution. Can you point me to the relevant provision?

Thanks,

Eoin.