Eric Goldman has recently blogged about a US case in which a local tv broadcaster was not held liable in defamation for a comment posted on its website by a viewer. More recently, Rebecca Tushnet discussed a case in which the review website Yelp was held not liable in defamation for hosting a review to which its subject objected (see also CYB3RCRIM3 | Eric Goldman | First Amendment Coalition | Internet Defamation Law Blog | Techdirt ). (Indeed, review authors will usually be able to rely on the defence of fair comment – or honest opinion – anyway). More recently still, Lilian Edwards has blogged about her presentation on internet intermediaries and legal protection. These posts got me thinking about how such disputes might play out as a matter of Irish law.

Eric Goldman has recently blogged about a US case in which a local tv broadcaster was not held liable in defamation for a comment posted on its website by a viewer. More recently, Rebecca Tushnet discussed a case in which the review website Yelp was held not liable in defamation for hosting a review to which its subject objected (see also CYB3RCRIM3 | Eric Goldman | First Amendment Coalition | Internet Defamation Law Blog | Techdirt ). (Indeed, review authors will usually be able to rely on the defence of fair comment – or honest opinion – anyway). More recently still, Lilian Edwards has blogged about her presentation on internet intermediaries and legal protection. These posts got me thinking about how such disputes might play out as a matter of Irish law.

[After the jump, I discuss the basic position at common law and under the Defamation Act, 2009 (also here), and then I compare and contrast US ‘safe harbor’ defences with EU immunities.]

A basic rule in defamation law is that anyone who is involved in the publication of a libel can be liable to the person defamed: in the case of a newspaper, this included not merely the journalist, editor and proprietor, but also the printer, the delivery van driver, and the newsagent. But this obviously casts the net of liability too widely, so the defence of innocent publication would apply to distributors who had no knowledge of the libel, where this absence of knowledge was reasonable. In the newspaper example, the newsagent and the van driver – at the very least – would usually benefit from this defence. These rules also apply equally online, so that an internet service provider hosting a defamatory website could be liable as a publisher of the website, unless the ISP had no knowlege of the defamation. So the defence of innocent dissemination could avail a general host. However, many ISPs filter their traffic in some way, and where they do so but let a defmatory statement through, it becomes harder for them to argue that they were not negligent, and the defence of innocent dissemination is unlikely to avail a host who is in some sense complicit in the publication of the statement. This is especially true of a moderator who actively approves the relevant statement. Moreover, once an ISP has knowledge of the defamatory content, the defence of innocent dissemination is no longer available for any continued hosting or publication.

This basic position has been reaffirmed by the Defamation Act, 2009 (also here): it acknowledges that an actionable statement can include an electronic communication or a statement published on the internet (see the definition of “statement” in section 2); it provides for a wide net of publication liability (section 6(2)); and it also provides for the defence of innocent publication (section 27).

On this basis, those who host content produced by others can be liable if that content is defamatory, unless they can rely on the defence of innocent publication; however, the more the hosts are involved in the publication of that content (as by filtering or moderating), the less likely it is that they can rely on the defence. Hence, if you submit a defamatory comment to a post on this blog, and if I moderate it, approve it and publish it, I can be liable with you in defamation. Scale this scenario up to encompass every ISP and online hosts, and there is a potentially enormous range of online liability. As a consequence, legislators in the US and the EU have moved to expand the range of defences open to ISPs and other hosts. In the US, the main provision is section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 (47 U.S.C. § 230). Section 230(c)(1) provides:

No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.

Given the threat that lawsuits pose to freedom of speech online, this section creates an immunity (a ‘safe harbor’) to any cause of action that would make service providers liable for information originating with a third-party user of the service (see, generally, David S Ardia “Free Speech Savior or Shield for Scoundrels: An Empirical Study of Intermediary Immunity Under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act” 43 (2) Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review (forthcoming, 2010) SSRN; and Volokh has recently blogged on updating the assumptions underlying the section.). And it was this immunity which was successfully asserted by the broadcaster in the cases mentioned by Eric Goldman and Rebecca Tushnet above. There is also a similar safe harbor immunity for ISPs hosting material that infringes copyright (see 17 U.S.C. § 512, enacted by Title II of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act).

In the EU, the equivalent defences are not as far reaching. Article 12 of the E-Commerce Directive (Directive 2000/31/EC) provides an immunity to ISPs who are “mere conduits” of information (provided that they have no role in the content of that information); and Article 14 provides an immunity to ISPs who simply host information, provided that

(a) the provider does not have actual knowledge of illegal activity or information and, as regards claims for damages, is not aware of facts or circumstances from which the illegal activity or information is apparent; or

(b) the provider, upon obtaining such knowledge or awareness, acts expeditiously to remove or to disable access to the information.

This Directive has been implemented in the UK and in Ireland (see the European Communities (Directive 2000/31/EC) Regulations 2003 (SI No 68 of 2003)). The safe harbours in the Directive are of general application, and are not limited to defamation or breach of copyright, so it is a very great pity that the Defamation Act, 2009 did not take the trouble to work out the interplay of the statutory defence of innocent publication with the EU’s general immunities for conduits and hosts (an issue which has proven very tricky in the UK).

Struan Robertson has recently argued that the EU’s immunities are corroding away. In his view, although the US safe harbors and the EU immunities are very similar in wording, their interpretations are diverging, so that European ISPs are at greater risk than their US counterparts of being saddled with liability for users’ transgressions. His discussion focuses on copyright, but since the EU immunities are generally cast, this analysis should also be applicable to defamation. However, the position in that context is not quite so pessimistic as all that.

For example, in the UK, the EU safe harbours have been successfully relied upon in defamation proceedings in Bunt v Tilley [2006] 3 All ER 336, [2006] EWHC 407 (QB) (10 March 2006) (hosts) (referred to in Gentoo Group v Hanratty [2008] EWHC 627 (QB) (07 April 2008) and Underhill v Corser [2010] EWHC 1195 (QB) (27 May 2010)) and in Metropolitan International Schools v Designtechnica Corp [2009] EWHC 1765 (QB) (16 July 2009) (search engines). And in Ireland, in Mulvaney v The Sporting Exchange Ltd trading as Betfair [2009] IEHC 133 (18 March 2009), Clarke J allowed the defendant to raise the EU safe harbours (the case is ongoing, but the substantive trial does not yet seem to have been heard; in the meantime, Clarke J’s judgment has been considered in the UK in Kaschke v Gray [2010] EWHC 690 (QB) (29 March 2010) (discussed by Emily Laidlaw here).

Betfair is a very important decision on the availability of the EU safe harbours at Irish law, and TJ has an excellent discussion of this issue here. In effect, Clarke J held that chatroom operators are hosts of user comments and thus entitled to raise the hosting immunity in Article 14 of the Directive as implemented in Regulation 18 of the 2003 Regulations, though whether they succeed at trial will depend on the actions they took when the impugned comments were drawn to their attention.

The question that struck me on reading Rebecca Tushnet’s post is whether an Irish review site would be able to rely on the EU safe harbours to defend a claim that a review posted on the site was defamatory. Similarly, the question that struck me on reading Eric Goldman’s post is whether an Irish broadcaster would be able to rely on the EU safe harbours to defend a claim that a comment posted on its website by a viewer was defamatory. Under the 2009 Act, the broadcaster and the review site are both publishers of the alleged defamatory content, so the main issues are whether the review site or the broadcaster have any potential defences.

Both might try to rely on the defence of innocent publication in section 27 of the 2009 Act. The broadcaster would be unsuccessful, since the comment is likely to have been moderated and approved. The review site might have more success, but – having regard to section 27(2)(c) – the prospects are unclear. Both might try to argue that they are simply conduits, and thus immune from liability under Article 12 of the Directive as implemented in Regulation 16 of the 2003 Regulations. In the copyright case of EMI v UPC (High Court, unreported, 11 October 2010; scribd) Charleton J held that the defendants constituted a mere conduit, in part because they did not select or modify the data (para 108). For that reason, the moderating broadcaster would fail, but the review site would have a better chance of establishing the defence. Finally, they would seek to argue that they were simply hosts for the purposes of Article 14 of the Directive as implemented in Regulation 18 of the 2003 Regulations.

To rely on Regulation 18, the broadcaster and the review site will have to demonstrate that they acted expeditiously to take the allegedly defamatory content down once its defamatory nature was brought to broadcaster’s attention. However, there is no definition of “expeditiously” in this context, and it is unclear whether taking some time to check the veracity of the comment before deciding that it is defamatory and only then taking it down will amount to sufficient expedition. Moreover, since it is likely that the broadcaster will have moderated the comments and that the review site will not, as TJ and Emily point out, such moderation may bring the broadcaster outside the scope of this safe harbour; indeed, even the fixing of spelling mistakes risks losing this protection.

Even if the broadcaster or the review site do not get a full defence on foot of one of the EU safe harbours, they may still be able to reduce its level of liability. For example, sections 24(1) and 31(4)(d) of the 2009 Act allow an apology made as soon as practicable after the defamation is brought to the defendant’s attention to mitigate the level of damages (though, as with “expeditious”, it is still unclear how the requirement to act “as soon as practicable” is affected by some investigation or consideration of the issue before issuing the apology). This is precisely the kind of context in which the US and EU practice is likely to diverge: in the US, the robust policy behind the safe harbor ensures that analysis is not bogged down in such minutiae; whereas, in the EU, they are unavoidable, and the ISPs run significant risks that they will thereby lose the benefit of the immunities. In any event, a prompt apology might induce a plaintiff wishing for a speedy resolution either to apply to the Press Ombudsman and the Press Council or to seek a declaratory order under section 28 of the Act.

Some of this might become a little clearer depending on what will happen on foot of an apology which currently appears on the Mechanical Turk blog on the Irish Times website:

Apology – Professor Patricia Casey

HUGH LENIHAN

Professor Patricia Casey

On May 22nd 2010, The Irish Times published in its print edition an article under the headline “Shorter childhoods mean sex education at home is vital”.

On May 23rd, a comment related to this article was moderated and published by The Irish Times on its website in the “have your say” section. The comment concerned Professor Patricia Casey. The allegations published in the comment were without foundation and were seriously defamatory of Professor Casey and have caused her great personal hurt and distress. The Irish Times accepts that Professor Casey is an internationally-respected psychiatrist of the highest standing and reputation.

Comments Off

Eric Goldman’s post suggests that this case would be decided in favour of the Irish Times in the US. However, there are so many unresolved issues in the EU safe harbours as implemented into Irish law that it is as yet entirely unclear as to how this case will be decided in Ireland if it proceeds to trial. Moreover, as Lilian Edwards points out, there are many new legal issues facing online intermediaries. So, watch this space; and in the meantime, go easy on the comments!

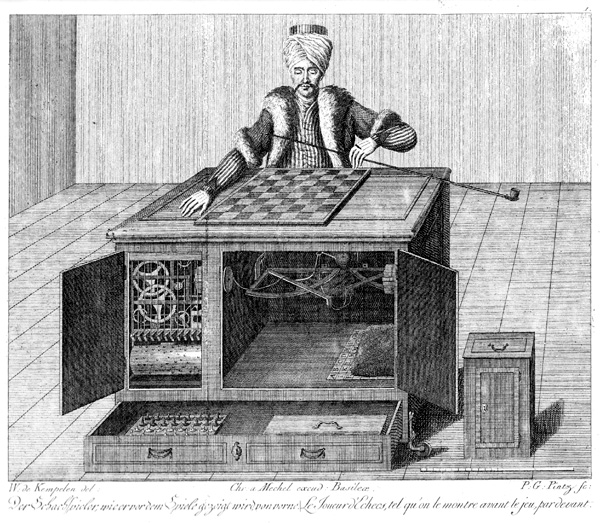

Update (28 March 2013): two recent stories on the BBC website tell more about the story of the Turk. First, Meet the Mechanical Turk, an 18th Century chess machine tells the story of a Californian who has built a working replica of the original automaton, which was accidentally destroyed by fire in 1854. Second, in A Point of View: Chess and 18th Century artificial intelligence, Adam Gopnik argues that the elaborate hoax had its own sense of genius:

We always over-estimate the space between the uniquely good and the very good. That inept footballer we whistle at in despair is a better football player than we have ever seen or ever will meet.

The few people who do grasp that though there are only a few absolute masters, there are many, many masters right below them looking for work tend, like [Johann] Maelzel [the first operator of the Turk], to profit greatly from it.

… It is very hard to do a difficult thing, it is very important to learn to do a difficult thing, and once you have learned to do it, you will always discover that there is someone else who does it better. The only consolation is that, often as not, those who do it best of all, are, one way or another, quite hollow inside. This seems like sage, if sober, wisdom to expect our children to master.

“Defamation” is a fine line for some comments posted online. You really have to be careful what you say online, even though there’s the “Communication Decency Act”.

There should be some alterations/additions done in the Communication Decency Act which would help to frame a liability of defaming comments on all those who are involved in the case of a social media publication.

This has already become a serious matter and countries like China have totally blocked social media websites to overcome any such issues.

Whether this is correct or wrong is a matter of debate but proper international laws should be in place and implemented as and when required to avoid further hazards erupting from social media.

Generally, anyone who repeats someone else’s statements is just as responsible for their defamatory content as the original speaker—if they knew, or had reason to know, of the defamation. Recognizing the difficulty this would pose in the online world, Congress enacted Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which provides a strong protection against liability for Internet “intermediaries” who provide or republish speech by others.

Copyright liability is or should be different than defamation, especially given the different structures of 47 USC 230 and 17 USC 512. An email marketing company was listed on Spamhaus’ ROSKO and sued for defamation and other torts in Illinois.

Is defamation easy to prove? Shouldn’t news reader then also be charged with defamation frequently for uttering defamatory comments? As internet and social media penetrates more into our life there is need for clear ans well defined laws, so that they are not misused by wrong intentions of people. Though a website is primarily responsible but in social interactive forums until there are complaints steps can’t be taken against comments and even some people want unwanted sentences about them out of the forum and complain to remove it.

The international law should be clear so that such cases can be dealt with. Many of them posts responses and articles on forums These should be directly published. They have to be checked for decency and then published. By doing this we can minimize such problems.

If the following tests are satisfied then a person can sue for defamation –

* The statement is likely to injure the reputation of the person by exposing them to ridicule, contempt or hatred.

* The statement is likely to make people shun or avoid them.

* The statement has the tendency to lower the person’s reputation in the estimation of others.

But Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act provides that no provider of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider. Thus, the publisher of a blog is generally not liable for comments by its readers.

Looking at it from perspectives as a commoner, I think that including the delivery guy or people in similar situation is too broad a net but it should include include all who were willing party to a defamation so that the guilty are identified and works as a deterrent for future incidents, the law should also be clear so that it is dealt justice fast and to the deserving. There are many people who lose a lot of credibility due to a media broadcast which is based on inferences that may not be true. Hope the blogs and forums will have an impact.

Defamation is a very broad term. There are no hard and fast rules for deciding about the same. But the law should be strict enough to catch erring people. As mentioned in another post Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act provides that no provider of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider. This tells us the publisher of a blog is not responsible for the comments published, but I strongly feel that the publisher should first filter the comments and then publish them.

In France the law is a bit more flexible: it is necessary that the comments of outsiders are reported on a blog and the author of the article will not be worried. Against by the French law of defamation applies outside the territory, if your blog is hosted abroad.