I was on the Marian Finucane show on RTE Radio 1 yesterday morning (listen here), discussing copyright in the National Anthem. The immediate context of the discussion was Senator Mark Daly‘s National Anthem (Protection of Copyright and Related Rights) (Amendment) Bill 2016 (reviving a Bill that he had introduced into the last Seanad earlier in the year). The story of the copyright in the national anthem is a fascinating one, with many legal twists and turns, which I will discuss in this post and the next (update: this post and the next were originally one post; but I have divided that post into two; in this post I discuss the copyright issues around the music and the English language version of the words of the anthem; in the next post, I will discuss the issues around the Irish language version). Once I have brought that story of these various versions of the anthem up to date, I will discuss the possible impact of Senator Daly’s Bill in a further post.

Working together in 1907, the music of the national anthem was composed by Patrick Heeney (1881-1911) and the English lyrics of “The Soldier’s Song” were composed by Peadar Kearney (1883-1942) [His first draft, written on copybook paper, sold at auction in 2006 for €760,000]. The text was first published in 1912; it quickly became a popular marching song among the Irish Volunteers; and it was sung by the rebels in the General Post Office during the 1916 Rising and later in the internment camps. The chorus was formally adopted as the rational anthem in 1926; as Ruth Sherry explains (with added links):

… a simple decision was made by the Executive Council to adopt “The Soldier’s Song” as the national anthem for all purposes. The reasons for choosing this rather than another air are not recorded, but it seems likely that by this point “The Soldier’s Song” had become so firmly established by custom that replacing it would prove difficult, and William Cosgrave is on record as wanting to retain it. The decision was not accompanied by any publicity, and was announced only by means of a brief answer to a backbencher’s question in the Dáil on 20 July 1926.

The Irish language version, “Amhrán na bhFiann“, was composed by Liam Ó Rinn in 1923 as a fairly free translation of Kearney’s English language text of “The Soldier’s Song”. This version gradually eclipsed the English language version; and, from the end of the 1930s, the chorus of “Amhrán na bhFiann” eventually took over completely as the national anthem in popular usage, though it seems never to have been formally adopted by the State. I will return to this version in my next post.

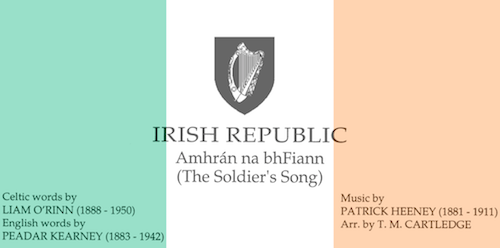

Unlike the flag, the national anthem is not provided for in the Constitution adopted in 1937. The image above is a mashup of an element of the sheet music (pdf) for the national anthem and the colours of the national flag (both taken from the historical information section of the website of the Taoiseach (the Prime Minister), and the versions in both languages appear on that sheet music.

The uncertainties surrounding the anthem include its copyright status. The almost-clandestine means by which “The Soldier’s Song” came to be adopted as the national anthem in 1926 meant that no negotiations were conducted with Kearney or with Heeney’s estate, and no royalties were paid to them. Kearney was understandably aggrieved, and sought royalties from the State. However, negotiations failed; and Kearney, and Heeney’s brother Michael, issued legal proceedings, a report of which from the Irish Press on 13 December 1932 appears on the right (I am grateful to the Gombeen Nation blog for the image). The case settled in 1933, and the State bought the rights to the music and the English lyrics for a total of £1,200 (pdf). But that was not the end of the story. There is a curious sequel, explained by Dr Seán Ryan, Minister for Finance, in the Dáil on 2 March 1965:

The uncertainties surrounding the anthem include its copyright status. The almost-clandestine means by which “The Soldier’s Song” came to be adopted as the national anthem in 1926 meant that no negotiations were conducted with Kearney or with Heeney’s estate, and no royalties were paid to them. Kearney was understandably aggrieved, and sought royalties from the State. However, negotiations failed; and Kearney, and Heeney’s brother Michael, issued legal proceedings, a report of which from the Irish Press on 13 December 1932 appears on the right (I am grateful to the Gombeen Nation blog for the image). The case settled in 1933, and the State bought the rights to the music and the English lyrics for a total of £1,200 (pdf). But that was not the end of the story. There is a curious sequel, explained by Dr Seán Ryan, Minister for Finance, in the Dáil on 2 March 1965:

The intention in buying out the existing rights [in the National Anthem in 1933] was to free the Anthem of vested interests and make it freely available for performance. That, as I said, appeared to be all right until recently it was realised that the right which was bought would lapse between 1967 and 1993. That was as a result of the Commercial Property Protection Act, 1959 which gave a right for 25 years after the person’s death. That is all the person could dispose of, for 25 years after his death, but his legal representatives would be entitled to benefit from the performance of this song and music between that and 1993; in other words for 25 years. When we realised this we had to set about buying the rights between 1967 and 1993. Eventually, we secured an agreement with the representatives of both Mr Peadar Kearney and Mr Michael Heaney and bought the rights for £2,500.

The government plainly apprehended that the period between 1967 and 1993 was a a gap of danger for its ownership of the copyright in the anthem. (The “gap of danger” is the “bearna baoil” which appears in both versions of the anthem; it is the only phrase in Irish in “The Soldier’s Song”, and it is repeated verbatim in “Amhrán na bhFiann). However, the Minister’s explanation of the gap is peculiar, for a number of reasons. I can find no Commercial Property Protection Act, 1959. There is an Industrial and Commercial Property (Protection) (Amendment) Act, 1958, which makes minor amendments to the Industrial and Commercial Property (Protection) (Amendment) Act, 1957, but I can find nothing similar for 1959. Nor can I find a section in an Act of that period that has the effect described by Minister.

Nevertheless, I have a theory. I suspect that the Minister’s exposition is a mangled description of the effect of section 9 of the 1957 Act. Section 156 of the Industrial and Commercial Property (Protection) Act, 1927 provided that the term of copyright was the life of the author plus fifty years, so that a work would come out of copyright on the first of January fifty years after the death of the author. However, a proviso to section 156 allowed in effect for a compulsory licence for the second twenty-five years of the post-mortem period. Section 9 of the 1957 Act essentially abolished this compulsory licence. Peadar Kearney died on 24 November 1942, which means that his works (including “The Soldier’s Song”) would come out of copyright on 1 January 1993, and that the second twenty-five years of the post-mortem period would run from 1 January 1967 to 1 January 1993. Given the Minister’s references to the period between 1967 and 1993, I assume that the 1933 settlement must have purchased the rights for the first twenty-five years of the post-mortem period (to 1 January 1967), intending to rely upon the compulsory licence in the proviso to section 156 of the 1927 Act for the second twenty-five years (from 1 January 1967 to 1 January 1993); and I assume further that the repeal of section 156 in 1957 therefore necessitated the purchase in 1965 of the rights in the second twenty-five years. This, at least, would explain the dates mentioned by the Minister. (I must stress that these are assumptions on my part, and if anyone who has read this far can shed any further light on the matter, I would be very grateful).

At this point, it is clear that, in 1965, the State owned the copyright in the English language lyrics “The Soldier’s Song”, and that this copyright would persist until 1 January 1993. However, from 1 July 1995, the copyright term was extended to the life of the author plus seventy years; so copyright now lasts until the first of January seventy years after the death of the author. The effect of the 1995 amendment was that “The Soldier’s Song” fell back into copyright until 1 January 2013.

So much for the lyrics. What of the music? Heeney died on 13 June 1911, which means that his music would have come out of copyright on 1 January 1962. If Heeney’s music and Kearney’s lyrics are considered a single work of joint-authorship, then section 166 of the 1927 Act would have provided that copyright in that work would have subsisted for “the life of the author who first dies” plus fifty years. Since Heeney died on 13 June 1911, this would have meant not only that Heeney’s copyright in the music would have come to an end on 1 January 1962 but also that Kearney’s copyright in the English language lyrics would likewise have come to an end on that date. However, section 10 of the 1957 Act provided that copyright subsisted in a work of joint-authorship for “the life of the author who dies last” plus fifty years. And since Kearney did not die until 24 November 1942, this meant not only that Kearney’s copyright in the English language lyrics would persist until 1 January 1993 but also that Heeney’s copyright in the music would likewise persist until that date. And when the copyright term was extended (as described in the previous paragraph) until 1 January 2013, that extension covered both the music and the English language lyrics.

The amendment effected by section 10 of the 1957 Act would therefore have provided another reason for the State to revisit the issue of the ownership of copyright in the national anthem. On the law as it stood when the 1933 deal was done, copyright in the national anthem would have lasted until 1 January 1962. This was changed by section 10 of the 1957 Act, which extended that copyright until 1 January 1993. However, this can’t have been the basis of the reason provided by the Minister for the 1965 deal, because he said he was concerned with the period from 1 January 1967, rather than the period from 1 January 1962.

In summary, then, the story of the copyright in the national anthem is a tangled one. But the position in which we now find ourselves is entirely clear. The State owned the copyright in the music and English language version (“The Soldier’s Song”) of the national anthem, and these copyrights persisted until 1 January 2013, when they lapsed by effluxion of time in the usual way. Senator Daly’s Bill would revive them “for an indefinite period”. This is a thoroughly bad idea, and I will explain why in a later post. Meanwhile, if anyone wants to emulate, with “Amhrán na bhFiann” or “The Soldier’s Song”, the Sex Pistols’ reworking of “God Save the Queen” or Jimi Hendrix’s Woodstock performance of “The Star Spangled Banner”, go right ahead. Unless and until Senator Daly’s Bill becomes law, this will not be an infringement of copyright in the national anthem. In my next post, I will discuss copyright issues relating to “Amhrán na bhFiann”, the Irish language version of the national anthem. In a subsequent post, I will explain why the Bill should not become law, so that any and all such re-imaginings of the national anthem should remain entirely possible, and indeed ought to be encouraged.

6 Reply to “Copyright and the National Anthem; unravelling a tangled past, avoiding a gap of danger – I – The Soldier’s Song”