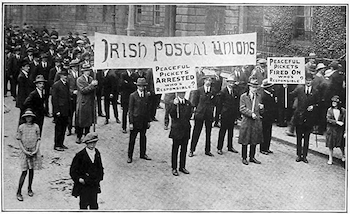

The Postal Strike, 9-29 September 1922 (see here and here) was the first major industrial dispute faced by the new government of the Irish Free State (see Gerard Hanley “They ‘never dared say “boo” while the British were here’: the postal strike of 1922 and the Irish Civil War” (2022) 46 (169) Irish Historical Studies 119). The government imposed various restrictions, including a ban on pickets. Nevertheless, the picture on the left (taken from The Graphic newspaper, 16 September 1922) shows the Postal Unions on the march in Dublin. More than a century later, the government continues to restrict the political activities of civil servants. In my previous post, we saw that the Civil Service Code of Standards and Behaviour (2004; revised 2008 (pdf); Circular 26/04 (09 September 2004) (pdf)) and Civil Servants and Political Activity (Circular 09/2009 (30 April 2009) (pdf)) provide for a blanket ban on civil servants engaging in any form of political activity or speaking in public on matters of local or national political controversy. My previous post considered whether the two circulars provided a sufficient legal basis for the ban. In this post, I want to consider whether the restrictions in the two circulars are constitutional.…

The Postal Strike, 9-29 September 1922 (see here and here) was the first major industrial dispute faced by the new government of the Irish Free State (see Gerard Hanley “They ‘never dared say “boo” while the British were here’: the postal strike of 1922 and the Irish Civil War” (2022) 46 (169) Irish Historical Studies 119). The government imposed various restrictions, including a ban on pickets. Nevertheless, the picture on the left (taken from The Graphic newspaper, 16 September 1922) shows the Postal Unions on the march in Dublin. More than a century later, the government continues to restrict the political activities of civil servants. In my previous post, we saw that the Civil Service Code of Standards and Behaviour (2004; revised 2008 (pdf); Circular 26/04 (09 September 2004) (pdf)) and Civil Servants and Political Activity (Circular 09/2009 (30 April 2009) (pdf)) provide for a blanket ban on civil servants engaging in any form of political activity or speaking in public on matters of local or national political controversy. My previous post considered whether the two circulars provided a sufficient legal basis for the ban. In this post, I want to consider whether the restrictions in the two circulars are constitutional.…

Author: Eoin

Political speech and civil servants – Part 1 – Blanket bans and ministerial circulars

In my previous two posts, I considered the drafting history and possible unconstitutionality of section 11 of the Defence (Amendment) Act 2024 (the 2024 Act; update: available here) (pdfs here and here). That section adds a new subsection (1A) to section 103 of the Defence Act, 1954 (the 1954 Act; consolidated here) placing comprehensive restrictions on the political speech of members of the Defence Forces. A similar blanket ban is imposed upon members of the civil service. In this post, I want to examine whether there is a sufficient legal basis for the ban. In my next post, I will consider whether that ban is constitutional.

In my previous two posts, I considered the drafting history and possible unconstitutionality of section 11 of the Defence (Amendment) Act 2024 (the 2024 Act; update: available here) (pdfs here and here). That section adds a new subsection (1A) to section 103 of the Defence Act, 1954 (the 1954 Act; consolidated here) placing comprehensive restrictions on the political speech of members of the Defence Forces. A similar blanket ban is imposed upon members of the civil service. In this post, I want to examine whether there is a sufficient legal basis for the ban. In my next post, I will consider whether that ban is constitutional.

The Civil Service Code of Standards and Behaviour (2004; revised 2008 (pdf); Circular 26/04 (09 September 2004) (pdf)) provides:

…5. Civil Servants and Politics

5.1 Restrictions have traditionally been imposed on civil servants engaging in political activity to ensure public confidence in the political impartiality of the Civil Service. This section restates the existing restrictions.5.2 … (d) All civil servants above clerical level are totally debarred from engaging in any form of political activity.

5.3 Civil servants in category (d) may not engage in public debate (e.g.

Political speech and the Defence Forces – Part 2 – Bright lines and the constitutionality of section 11 of the Defence (Amendment) Act 2024

Having considered the Defence (Amendment) Bill 2024 (the Bill) and the advice of the Council of State (pictured left), on Wednesday, 17 July 2024, the President signed the Bill and it accordingly become law as the Defence (Amendment) Act 2024 (the 2024 Act; update: available here). Section 103(1) of the Defence Act, 1954 (consolidated here) (the 1954 Act) provides that members of the Permanent Defence Force from “shall not join, or be a member of, or subscribe to, any political organisation or society”. Section 11 of the 2024 Act adds a new subsection (1A) to section 103 of the 1954 Act, providing that a member of the Permanent Defence Force shall not:

Having considered the Defence (Amendment) Bill 2024 (the Bill) and the advice of the Council of State (pictured left), on Wednesday, 17 July 2024, the President signed the Bill and it accordingly become law as the Defence (Amendment) Act 2024 (the 2024 Act; update: available here). Section 103(1) of the Defence Act, 1954 (consolidated here) (the 1954 Act) provides that members of the Permanent Defence Force from “shall not join, or be a member of, or subscribe to, any political organisation or society”. Section 11 of the 2024 Act adds a new subsection (1A) to section 103 of the 1954 Act, providing that a member of the Permanent Defence Force shall not:

…(a) while in uniform or otherwise making himself or herself identifiable as a member of the Permanent Defence Force—

(i) make, without prior authorisation from the member’s commanding officer, a public statement or comment in relation to a political matter or matter of Government policy, or

(ii) attend a protest, march or other gathering in relation to a political matter or matter of Government policy,(b) canvass on behalf of, or collect contributions for, any political organisation or society, or

(c) address a meeting of a political organisation or society.

Political speech and the Defence Forces – Part 1 – The apolitical nature of the Defence Forces and the legislative history of section 11 of the Defence (Amendment) Act 2024

Having considered the Defence (Amendment) Bill 2024 (the Bill) and the advice of the Council of State (pictured left), the President yesterday (Wednesday, 17 July 2024) signed the Bill and it accordingly become law as the Defence (Amendment) Act 2024 (the 2024 Act; update: available here) (see Irish Times, 17 July 2024). Articles 31 and 32 of Bunreacht na Éireann provides provides for a Council of State to aid and counsel the President. Article 26 provides that the President may, after consultation with the Council of State, refer a Bill to the Supreme Court for a decision on its constitutionality. Last Monday, 15 July 2024, the President convened a meeting of the Council of State (pictured left), to hear from the Council regarding the constitutionality of the Defence (Amendment) Bill 2024. In a statement in advance of the meeting, the President said that he intended “to consult the Council of State in particular on Sections 11 and 24 of the Bill and whether the interference with constitutional rights is disproportionate” (see Irish Times, 12 July 2024). Section 11 of the Bill (now Act) restricts the Article 40.6.1(i) right to political expression of a member of the Permanent Defence “while in uniform or otherwise making himself or herself identifiable as a member of the Permanent Defence Force”.…

Having considered the Defence (Amendment) Bill 2024 (the Bill) and the advice of the Council of State (pictured left), the President yesterday (Wednesday, 17 July 2024) signed the Bill and it accordingly become law as the Defence (Amendment) Act 2024 (the 2024 Act; update: available here) (see Irish Times, 17 July 2024). Articles 31 and 32 of Bunreacht na Éireann provides provides for a Council of State to aid and counsel the President. Article 26 provides that the President may, after consultation with the Council of State, refer a Bill to the Supreme Court for a decision on its constitutionality. Last Monday, 15 July 2024, the President convened a meeting of the Council of State (pictured left), to hear from the Council regarding the constitutionality of the Defence (Amendment) Bill 2024. In a statement in advance of the meeting, the President said that he intended “to consult the Council of State in particular on Sections 11 and 24 of the Bill and whether the interference with constitutional rights is disproportionate” (see Irish Times, 12 July 2024). Section 11 of the Bill (now Act) restricts the Article 40.6.1(i) right to political expression of a member of the Permanent Defence “while in uniform or otherwise making himself or herself identifiable as a member of the Permanent Defence Force”.…

Settlement in HKR Middle East Architects Engineering LC v English

In three extensive posts on this blog (here, here, and here), I looked at issues arising out of McDonald J’s judgments in HKR Middle East Architects Engineering LC v English (No 1) [2019] IEHC 306 (10 May 2019); (No 2) [2021] IEHC 142 (3 March 2021); (No 3) [2021] IEHC 376 (31 May 2021). The facts were colourful, and the legal issues were extensive; the subset relevant to this blog included restitution for unjust enrichment by means of a failure of basis (formerly total failure of consideration), the quantification of enrichment, and the potential availability of an automatic resulting trust.

In three extensive posts on this blog (here, here, and here), I looked at issues arising out of McDonald J’s judgments in HKR Middle East Architects Engineering LC v English (No 1) [2019] IEHC 306 (10 May 2019); (No 2) [2021] IEHC 142 (3 March 2021); (No 3) [2021] IEHC 376 (31 May 2021). The facts were colourful, and the legal issues were extensive; the subset relevant to this blog included restitution for unjust enrichment by means of a failure of basis (formerly total failure of consideration), the quantification of enrichment, and the potential availability of an automatic resulting trust.

I note from today’s Irish Times that the case has now been settled (with added links):

…Settlement reached in Middle Eastern firm’s case against businessman

Matter resolved in out-of-court discussions, judge told

Aodhan O’Faolain

A resolution has been reached in a long-running commercial court action brought by a Middle Eastern engineering and architecture firm against businessman Barry English over alleged unjust enrichment.

The action was launched in 2017 by Hogan Keoghan Ryan Middle East Architects Engineering LLC (HKRME) against Mr English, the founder of Winthrop Engineering, who had denied all the claims against him.

Vidal v Elster; Trump too small; and Thomas too small-minded

In Vidal v Elster 602 US 286 (2024) (pdf), the US Supreme Court yesterday upheld the refusal of the US Patent and Trademark Office to register “Trump too small” as a trademark. In his opinion for the Court, Thomas J proved himself small-minded both in his approach to First Amendment analysis in general and in his approach to the fraught inter-relationship of trademark restrictions and the First Amendment in particular.

In this case, the plaintiff, Steve Elster, sought trademark protection for t-shirts featuring the slogan “Trump too small” (pictured above left). The slogan refers to a debate in the 2016 presidential primaries when Senator Marco Rubio teased Donald Trump about the size of his hands (with implications about other features). The plaintiff wanted to use it to criticize President Trump in general, and, specifically, to convey “that some features of President Trump and his policies are diminutive”. Section 1052(c) of the Lanham Act (Trademark Act, 1946) (15 USC § 1052(c)) precludes registration of a trademark that (emphasis added):

consists of or comprises a name, portrait, or signature identifying a particular living individual except by his written consent, …

As a consequence of this “names” clause, an examiner from the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) refused the plaintiff’s application to register “Trump too small”, and the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) affirmed.…

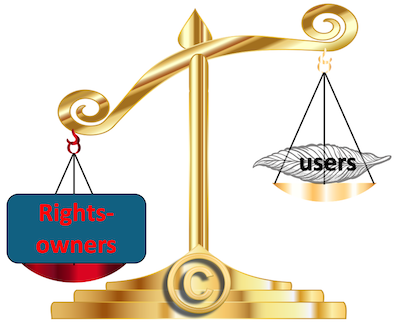

Copyright balance, technological protection measures, rights management information, and fair dealing

The law of copyright seeks to balance the interests of various members of the copyright community: the authors of copyright works, the big content companies to which they license or transfer their rights, and the societies which collect their royalties; platforms and intermediaries which facilitate online distribution of and access to copyright content; and users (whether individual, or heritage, or education, etc) who wish not only to use but to build upon existing works. Legislation such as the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000 [CRRA], and the InfoSoc Directive (Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society (OJ L 167, 22.6.2001, p. 10–19)), have sought to get these balances right, but are often criticised for failing to strike them in appropriate places.

The law of copyright seeks to balance the interests of various members of the copyright community: the authors of copyright works, the big content companies to which they license or transfer their rights, and the societies which collect their royalties; platforms and intermediaries which facilitate online distribution of and access to copyright content; and users (whether individual, or heritage, or education, etc) who wish not only to use but to build upon existing works. Legislation such as the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000 [CRRA], and the InfoSoc Directive (Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society (OJ L 167, 22.6.2001, p. 10–19)), have sought to get these balances right, but are often criticised for failing to strike them in appropriate places.

Again, it was a theme of Modernising Copyright (2013) (pdf, via here), the Report of the Copyright Review Committee [CRC Report], that reforms to the 2000 Act should balance the interests of all of the various members of the copyright community (full disclosure, I was the Chair of that committee). So, for example, in the context of technological measures for the protection of copyright or for the management of copyright information, the CRC Report recommended not only that the legal rules underpinning such measures be strengthened, but also that there would be a practical remedy where such measures operated to prevent someone from undertaking acts permitted by the exceptions provided in the copyright legislation.…

Duress in Contract and Restitution for Unjust Enrichment: Lessons from Mistake

Via Steve Hedley‘s Private Law Theory blog, I am delighted to learn of Charmaine Chang “When a Contract Falls Short: A Special Case for Restitution under Duress in Unjust Enrichment” (2024) 6 City Law Review 30 (CityLR (pdf) | SSRN); the abstract provides

Via Steve Hedley‘s Private Law Theory blog, I am delighted to learn of Charmaine Chang “When a Contract Falls Short: A Special Case for Restitution under Duress in Unjust Enrichment” (2024) 6 City Law Review 30 (CityLR (pdf) | SSRN); the abstract provides

…The English law of unjust enrichment deals with situations where it is unjust for someone to receive a benefit without paying for it. Duress is one of the unjust factors that allows for restitution.

The recent approach of the court assumes the same test for duress in contract and unjust enrichment as in CTN Cash and Carry. This is problematic in cases where there are no valid contracts in play. First, this obscures the normative foundation of unjust enrichment. The higher threshold for establishing duress in contract law is justified by its own principles and aims which are not present in unjust enrichment. Second, the existing grounds of recovery that centre on the application of pressure to the claimant and third-party cases in duress show that duress in unjust enrichment is primarily claimant-sided. It is not concerned with the reprehensible conduct of the defendant.

This article argues for a lower threshold to establish duress in unjust enrichment.