“Immanuel Kant should be banned…”

I’m struggling to think of the last time I heard anyone in Scottish politics say “I believe in free expression“, without following it with a “but”, or some other pious caveat, justifying illiberal legislation to put peoples’ tongues in the vice, fetter their fingers, or otherwise curtail free speech. This is not a uniquely Scottish phenomenon, of course. The whole rhetoric of balancing rights against one another lends itself to this sort of discourse, where one can simultaneously avow your watery support for a range of competing propositions – free speech, protection of minorities from “hate”, public order – and having recognised a range of entangled interests, and completed the relevant obeisances to all sides, unembarrassedly legislate, untroubled by dissonances as you obliterate the substance of liberty. All of which is done with a greasy air of self-justification and secular homily; a ludicrous pantomime parade of beetled brows and serious faces, as pompous moral vocabularies are dusted off to justify a range of reactionary reforms. Politicians assume grave airs to have their photos snapped by Amnesty International – all too happy to condemn repressive regimes abroad for jailing bloggers, writers, speakers – but seem to struggle to find the time even to shrug about domestic outrages.

Author: Eoin

Hyperlinks and defamation in the Supreme Court of Canada

Crookes v Newton 2011 SCC 47 (CanLII) (19 October 2011)

From the headnote (emphasis added):

To prove the publication element of defamation, a plaintiff must establish that the defendant has, by any act, conveyed defamatory meaning to a single third party who has received it. Traditionally, the form the defendant’s act takes and the manner in which it assists in causing the defamatory content to reach the third party are irrelevant. Applying this traditional rule to hyperlinks, however, would have the effect of creating a presumption of liability for all hyperlinkers. This would seriously restrict the flow of information on the Internet and, as a result, freedom of expression.

Hyperlinks are, in essence, references, which are fundamentally different from other acts of “publication”. Hyperlinks and references both communicate that something exists, but do not, by themselves, communicate its content. They both require some act on the part of a third party before he or she gains access to the content. The fact that access to that content is far easier with hyperlinks than with footnotes does not change the reality that a hyperlink, by itself, is content neutral. Furthermore, inserting a hyperlink into a text gives the author no control over the content in the secondary article to which he or she has linked.

For consumers, three is a magic number

|

Like the old joke about buses, you wait for ages, then three come along at once. So it is with consumer protection initiatives. There have been three in the past week. First, the EU Commission last week proposed a new Directive on Consumer Rights, which would merge various existing Directives and update and modernise EU consumer protection rules (hot on the heels of a slightly broader proposed Common European Sales Law). Second, the Minister for Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation yesterday announced the enactment of a comprehensive Consumer Rights Act, implementing the Report (pdf) of the Sales Law Review Group. As with the new Directive, the new Act will also merge various existing Irish pieces of legislation, and then update and strengthen Irish consumer protection law. Third, the Central Bank of Ireland today published a revised Consumer Protection Code (pdf), to ensure that consumers are adequately protected in their dealings with financial institutions. This is all very welcome, and I look forward to when these three initiatives come into force.…

Philosophical questions about fascism and free speech

|

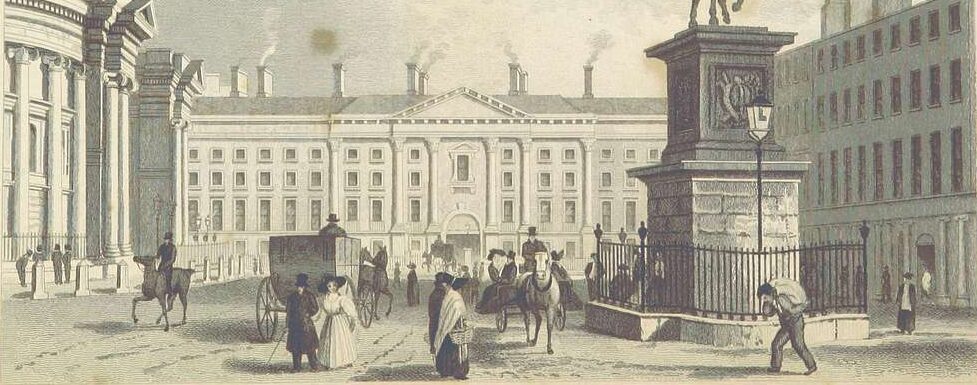

Last Tuesday, in the My Education Week column in the Irish Times, Paddy Prendergast, the Provost of Trinity College Dublin (and thus my boss) wrote a diary of his working week. This is how his entry for Wednesday, October 5th, began (with added links):

I meet with the Senior Dean and Dean of Students to discuss the student debating society, the Philosophical Society’s invitation to the BNP leader, Nick Griffin, to participate in a debate later this month. The issue has received considerable media coverage, but more importantly there are objections from our own college community. Freedom of speech is an important principle as is that of self-governance of student societies. We agree to meet with the Philosophical Society and consider this serious matter further. …

This seemed positive enough. Both freedom of speech and student society self-governance would pull in favour of allowing Nick Griffin to speak. Don’t get me wrong: Griffin’s views are loathsome, and the BNP is a hateful organisation, but I defend their right to spew their foul and horrid bile simply so that it can be exposed for the obnoxious and indefensible nonsense that it is. But this debate is not to be.…

Tom Hickey defines the “Common Good”

Opportunity to reclaim the idea of ‘republic’

… Citizens of an authentic republic are committed to the fact that they share a social and political community with other citizens. They appreciate that their own individual good, and the good of their families and local communities, is intimately connected with the common good of the republic.

Moreover, this common good is not a crude aggregation of competing private goods. It requires meaningful deliberative engagement on the part of all citizens, and participation. But this participation must be based on public-spiritedness, not on ambitions for the advancement of private interests. …

The phrase “the common good” is used several times in Bunreacht na hEireann, as a ground for limiting rights. In that context, in the hands of litigants and judges, it is often treated as simply a synonym either for a utilitarian preference for the greatest good of the greatest number or for the interests of the State. Tom’s summary demonstrates that neither view is correct.

The Free Speech Blog: Official blog of Index on Censorship » Is nothing sacred?

… at the launch of Index’s on Censorship magazine’s “Art Issue” on Wednesday at the Free Word Centre … [a]rtists Langlands & Bell gave a firsthand account of what it was like to have their work censored by the Tate despite their willingness to alter parts of the work to ensure the gallery was not in contempt of court. Ben Langlands spoke of the frustration they felt at not being able to show their work in its entirety – and with Tate for not being transparent about the reasons behind the removal of their film ”Zardad’s Dog”, part of their Turner-nominated The House of Osama Bin Laden.

Atque in perpetuum, Stephane, ave atque vale

Great post on < mooseabyte >: Deciding on our own digital death or forever stuck in the clouds?

It is a fact not in need of repetition that we all die. But our online lives, through lack of individual management and frequent lack of online service providers (OSPs) guidance, do not fully reflect this fundamental certainty. Admittedly in the social networking world there is greater awareness, with online reminders of the fragility of life through memorialised Facebook profiles. This practice, in stark contrast to the conventional slab of engraved granite, provides an easily accessible and virtual memorial to the deceased user. It is also a practical response which stops the issues caused by friends of a deceased Facebook user being urged to get in touch and reconnect with a dead friend, causing clear emotional upset (see report here). But, overall many OSPs don’t have sufficient provisions in place for managing a user’s digital assets upon death. Coupled with lack of user awareness this creates a problem which will grow in significance as online service users get older.