When it was handed down, I described the decision of Phelan J in Tallon v Director of Public Prosecutions [2022] IEHC 322 (31 May 2022) as an important judgment on the scope of the rights to freedom of expression and communication protected by the Constitution. It concerned the extent to which an anti-social behaviour order imposed pursuant to section 115(1) of the the Criminal Justice Act, 2006 (also here) could permissibly restrain those rights.

When it was handed down, I described the decision of Phelan J in Tallon v Director of Public Prosecutions [2022] IEHC 322 (31 May 2022) as an important judgment on the scope of the rights to freedom of expression and communication protected by the Constitution. It concerned the extent to which an anti-social behaviour order imposed pursuant to section 115(1) of the the Criminal Justice Act, 2006 (also here) could permissibly restrain those rights.

The Wexford District Court imposed an ASBO on the applicant prohibiting him from engaging in public speaking and recording anywhere within the environs of Wexford Town at any time. On a judicial review to the High Court, Phelan J quoted extensively from Barrington J’s judgment in Murphy v Irish Radio and Television Commission [1999] 1 IR 12, 24, [1998] 2 ILRM 360, 372 (28 May 1998) (doc | pdf) on the free speech rights protected by the Constitution. She held that those rights were engaged, and that the restraint of anti-social behaviour was a legitimate reason to justify the ASBO, but that the order was disproportionate. She therefore held that the ASBO made under section 115 of the Act was ultra vires, and she quashed two convictions (under section 117 of the Act (also here)) for breaching the ASBO. However, although a challenge to the constitutionality of that section was included in the statement of claim, Phelan J held that, since the applicant had succeeded on the vires issue, it was not necessary to address the constitutional issue ([134]).

Alerted this morning by the always valuable Decisis.ie, I see that the Court of Appeal has dismissed the applicant’s appeal: [2023] IECA 125 (25 May 2023) (Donnelly J; Edwards and McCarthy JJ concurring) (noted here and here). Although that judgment was handed down on 25 May 2023, it was not uploaded to Courts.ie until last Friday, 20 June 2025. My analysis here of the judgment of the Court of Appeal draws on my analysis (also here) of the judgment at first instance, and these two posts should be read together.

The ASBO in question ordered that the applicant “prohibited from engaging in public speaking and recording anywhere within the environs of Wexford Town including North Main Street Bullring, Selksker Square at any time”. Phelan J concluded that the applicant’s constitutional rights, including the rights to freedom of expression and communication, were engaged by this prohibition, and there was no appeal from this conclusion. Instead, the DPP and the State argued that the applicant was not entitled to relief by way of judicial review because that is a discretionary remedy and he had not exhausted his alternative remedies, including the jurisdiction of the District Court to vary a civil order under section 115(7), and the his right to appeal against the convictions. This submission had not found favour with Phelan J at first instance (eg [84]), and it did not find favour with Donnelly J on appeal (eg [97]).

The ASBO in question ordered that the applicant “prohibited from engaging in public speaking and recording anywhere within the environs of Wexford Town including North Main Street Bullring, Selksker Square at any time”. Phelan J concluded that the applicant’s constitutional rights, including the rights to freedom of expression and communication, were engaged by this prohibition, and there was no appeal from this conclusion. Instead, the DPP and the State argued that the applicant was not entitled to relief by way of judicial review because that is a discretionary remedy and he had not exhausted his alternative remedies, including the jurisdiction of the District Court to vary a civil order under section 115(7), and the his right to appeal against the convictions. This submission had not found favour with Phelan J at first instance (eg [84]), and it did not find favour with Donnelly J on appeal (eg [97]).

The appellants also argued that the ASBO was sufficiently clear and certain to be intra vires section 115. Again, this submission had not been successful before Phelan J at first instance (eg [110]), and it was not successful on appeal: “applying the principle that an order that imposes an obligation to abide by it on pain of criminal sanction, must be clearly expressed and indicate precisely what the subject of the order is required to do or refrain from doing, … this civil order was correctly held by the High Court to violate the principle of legal certainty” ([115] Donnelly J).

Although it was not necessary to address the issue, ([117]) Donnelly J noted (obiter) that the issue of the proportionality of the particular sentence “ought not to have been considered by the trial judge as a standalone ground for quashing the convictions” ([118]). In my analysis of her judgment, I did not read Phelan J as considering whether the sentence imposed for breach of the ASBO was proportionate (on the issue of proportionality in sentencing, see, eg, People (DPP) v M [1994] 3 IR 306, 317 (Denham J); DPP v Molloy [2021] IESC 44 (19 July 2021) [21] (Charleton J)). Instead, I read her as considering the prior question whether the ASBO itself was a proportionate restriction upon the applicant’s constitutional rights, in the sense advanced by Costello J in Heaney v Ireland [1994] 3 IR 593, 607-608, [1994] 2 ILRM 420, 431-432 (aff’d [1996] 1 IR 580, 598-590, [1997] 1 ILRM 117, 126-127 (O’Flaherty J; Hamilton CJ, and Blayney, Denham and Barrington JJ concurring)), and as applied by Barrington in the context of restrictions on the constitutional protections of freedom of expression and communication in Murphy v Irish Radio and Television Commission [1999] 1 IR 12, [1998] 2 ILRM 360, (28 May 1998) (doc | pdf) (Barrington J; Hamilton CJ and O’Flaherty, Denham, and Keane JJ concurring). First, this is clear from the heading of her analysis of the issue: “Restriction on Fundamental Right to Communicate and the Proportionality Test”, and of her initial observation under this head that she was considering constitutional rights “safeguarded under the Constitution against arbitrary or disproportionate interference” ([116]). Second, she referred to Heaney ([118]) and Murphy ([120]) (rather than to cases like M and Molloy), and she commented that, in the application of section 117, the Courts must exercise their powers “in a constitutionally compliant manner and having due regard to the requirements of the doctrine of proportionality” ([121]). Third, she explained this doctrine as requiring, inter alia, that the ASBO should impair the various constitutional rights engaged “as little as possible” ([124]); it should be “tailored closely” to the anti-social behaviour ([125], see also [129], [136]); and it should “extend[] no further than is necessary to restrain a recurrence of offending behaviour” (ibid). However, the ASBO made in this case “was not sufficiently tailored, targeted, clear, narrowly drawn or precise and for that reason resulted in an unconstitutional interference with the applicant’s rights” ([131]); hence, “the failure to tailor the order to the offending behaviour result[ed] in a disproportionate interference with the applicant’s personal rights” ([136]). Again, since she found that the terms of ASBO went “beyond what was required”, she concluded that “it must fail a proportionality test” ([124]); it was disproportionate insofar as it “interfere[d] excessively with the applicant’s constitutionally protected rights” ([130]).

In all of this, it is perfectly clear that Phelan J was applying the rubric of proportionality in Heaney and Murphy. However, she did comment, in passing, that the case “also raises potential issues concerning the principle of proportionality in sentencing” ([122]). However, the words emphasised here make it clear that this was obiter: these were “potential” issues, rather than matters analysed in the case; and they were matters which “also” arose, additional to the main issue being dealt with in this section of the judgment, which was proportionality in the Heaney/Murphy sense. Hence, Donnelly J’s obiter about Phelan J’s obiter about proportionality of sentencing was unnecessary, and it should not be read as impugning Phelan J’s analysis that the applicant’s constitutional rights were disproportionately infringed by the terms of the ASBO. Indeed, the starting point in the Court of Appeal was that the applicant’s constitutional rights were indeed infringed, and the appeal turned on the nature of the remedy.

At first instance, Phelan J considered that, since the applicant had succeeded in his challenge to the ASBO, it was not necessary to decide the question of whether section 117 was unconstitutional. On appeal, Donnelly J agreed ([123]-[124]):

the constitutional rights to freedom of expression, to freedom of conscience and to free profession and practice of religion are subject to public order and morality. Furthermore, the State has to guarantee in it laws to respect and, as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate the right[s] of the citizen. This may entail a balancing of rights. … I consider that the more appropriate approach is to restrain from expressing any views as to the constitutionality of the legislation.

Hence, whilst section 117 on its face was not struck down, its application to the ASBO on the facts was unconstitutional. In challenges to restrictions upon constitutional rigths, the US Supreme Court often distinguishes between facial challenges and as-applied challenges. A successful facial challenge to finds the restriction unconstitutional in every application, and it is struck down as void and of no effect. A successful as-applied challenge finds the restriction unconstitutional only as applied to the individual, leaving it otherwise intact (see, generally, Moody v NetChoice, LLC and NetChoice, LLC v Paxton 603 US 707 (2024)). In these terms, the challenge in Tallon was a successful as-applied challenge, as it related only to to the ASBO made on foot of the application of section 115 on the facts. Since that as-applied challenge was successful, it was not necessary to consider the facial challenge, and both Phelan J at first instance and Donnelly J on appeal did not do so.

In the US, the Supreme Court usually prefers to consider as-applied challenges to legislation, rather than facial challenges, except in the First Amendment context, where they are far more willing to consider facial challenges (I have discussed here a high profile case in which the plaintiff sought to make both facial and as-applied First Amendment challenges). Indeed, in this context, the overbreadth doctine may be a specific example of a facial challenge (see the aptly-named Broadrick v Oklahoma 413 US 601 (1973)). By this doctrine, a restriction upon speech will be unconstitutionally overbroad where it sweeps too broadly and penalizes a substantial amount of constitutionally protected speech (Reno v ACLU 521 US 844 (1997)).

There are hints of this in Tallon: Phelan J held that the ASBO was “overly broad” ([124], see also [130]). and that it infringed the applicant’s constitutional rights “by reason of … over reach” ([130]). However, these references to overbreadth are effectively synonymous with findings of a lack of proportionality rather than an assertion of a separate doctrine of overbreadth (cp, eg, Blehein v Minister for Health & Children [2009] 1 IR 275, 281, [2008] IESC 40 (10 July 2008) [18] (Denham J; Hardiman, Geoghegan, Kearns and Macken JJ concurring) (limitation on a right “should not be overbroad, should be proportionate, and should be necessary to secure the legitimate aim”)). On appeal in Tallon, Donnelly J considered that “if the breadth of the order is unclear, it may be said to be overbroad and transgress the principle of legal certainty. In my view, it is in this … sense that the civil order was impugned by the High Court in its finding that the order did not comply with the requirements of legal certainty inherent in the protection of due process rights” ([105]). And she held that, since the ASBO was “vague and impermissible” ([115]), it “was correctly held by the High Court to violate the principle of legal certainty” ([ibid]). Again, this references to overbreadth is effectively synonymous with findings of a lack of certainty in the terms of the ASBO. Since that the case turned on as-applied challenge, then, neither at first instance, nor on appeal, can the references to overbreadth be incipient examples of the US doctrine. Indeed, that doctrine does not seem otherwise to have gained a foothold at Irish law (see, eg, David Kenny “A Dormant Doctrine of Overbreadth: Abstract Review and Ius Tertii in Irish Proportionality Analysis” (2010) 37(1) Dublin University Law Journal (ns) 24 (Academia)).

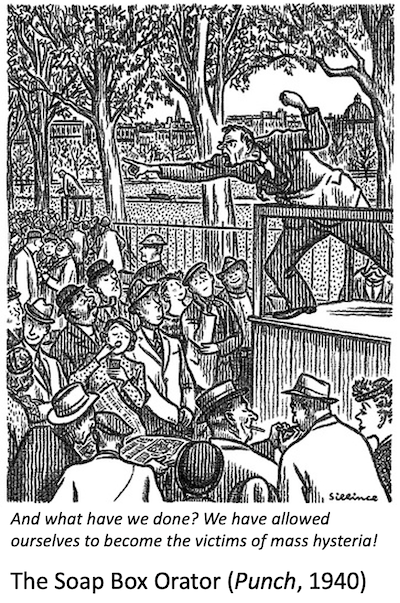

Finally, the breadth of the ABSO savours not only of disproportionality and uncertainty, but also of prior restraint. In the US, the Supreme Court has interpreted the First Amendment as affording “special protection against orders that prohibit the publication or broadcast of particular information or commentary – orders that impose a ‘previous’ or ‘prior’ restraint on speech” (Nebraska Press Association v Stuart 427 US 539, 556 (1976) (Burger CJ)). The ASBO in question in Tallon prohibited the applicant “from engaging in public speaking and recording anywhere within the environs of Wexford Town … at any time”. This was not an order directed the to actual mischief caused by the applicant’s speech; it was a complete prohibition on the applicant’s future speech in Wexford, and thus constituted a prior restraint. The US Supreme Court considers that prior restraints are presumptively unconstitutional (New York Times v United States 403 US 713, 714 (1971) (“Any system of prior restraints of expression comes to this Court bearing a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity” (per curiam)). Permanent injunctions after a full trial on the merits, such as those in defamation cases not to repeat the libel, (for all their flaws) do not amount to prior restraints; but they are strictly limited to orders not to repeat specific allegations. However, broader prohibitions, such as those not to talk at all about the defamation plaintiff, would amount to unconstitutional prior restraints. Even those broader injunctions are nowhere near as extensive as the ASBO in Tallon, which would plainly amount, in US terms, to an unconstitutional prior restraint.

In Observer & Guardian v UK 13585/88, (1992) 14 EHRR 153, [1991] ECHR 49 (26 November 1991), the UK government attempted prevent the publication of Peter Wright Spycatcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer (Heinemann (Australia); 1987), and the European Court of Human Rights held ([80]) that Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights “does not in terms prohibit the imposition of prior restraints on publication, as such” but “the dangers inherent in prior restraints are such that they call for the most careful scrutiny on the part of the Court”. In Mahon v Post Publications [2007] 3 IR 338, [2007] IESC 15 (29 March 2007) [65]-[66] Fennelly J (Murray CJ and Denham J concurring) followed Observer & Guardian v UK. Hence, as a matter of Irish law, even if prior restraints are not presumptively unconstitutional, they nevertheless call for the most careful scrutiny. Some restrictions will survive such scrutiny; for example, where a permanent injunction not to repeat a libel is awarded after a close and penetrating examination of the facts, this will amount to a necessary and proportionate restriction upon constitutional speech rights. But there seems to have been no such analysis when the District Court imposed the ASBO upon the applicant in Tallon. And the analyses by Phelan J in the High Court and Donnelly J in the Court of Appeal make it clear that the ASBO would fail the necessary careful scrutiny.

Tallon clearly raises interesting questions canvassed in my post on the decision of Phelan J at first instance as well as in this post. However, the Supreme Court seems to have made no determination, pursuant to Article 34.5.3 of the Constitution, on the questions whether the decision of the Court of Appeal “involves a matter of general public importance”, or whether “it is in the interests of justice” that there be an appeal. Hence, there will be no further appeal from the Court of Appeal to the Supreme Court. And I won’t be surprised by a judgment noted on Decisis.ie, having being posted two years late on Courts.ie!