In yesterday’s Irish Independent, Dearbbail McDonald reported that the public will get better access to court documents under plans being considered by the Government:

Ireland is unique among countries with a common law system as it does not provide access to court documents. Members of the public, as well as the media, have no way of securing access to documents, including court statements and legal submissions, that are opened and relied on in legal proceedings. …

The lack of access to court files has been raised in submissions to amend the forthcoming Legal Services Regulation Bill.

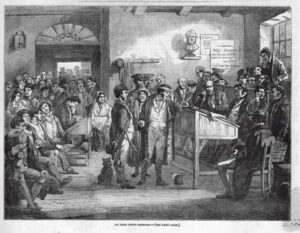

The image left is of the Irish Petty Sessions Court, taken from the Illustrated London News in February 1853, and it shows open justice at its best: a packed courtroom, with a full crowd following the proceedings. The Petty Sessions Court was established by the Petty Sessions (Ireland) Act, 1851; and it has long since been subsumed within the District Court.

The image left is of the Irish Petty Sessions Court, taken from the Illustrated London News in February 1853, and it shows open justice at its best: a packed courtroom, with a full crowd following the proceedings. The Petty Sessions Court was established by the Petty Sessions (Ireland) Act, 1851; and it has long since been subsumed within the District Court.

I have referred to aspects of the Legal Services Regulation Bill, 2011 already on this blog; and I hope that this welcome and significant development will find a legislative home when the Bill becomes law. Strictly speaking, this is unnecessary, as there already exist various rights of access to such material, at common law, under the European Convention on Human Rights, and under the Constitution; but an addition to these rights is very welcome.

For example, at common law, the Court of Appeal in R (on the application of Guardian News and Media Ltd) v City of Westminster Magistrates’ Court [2012] EWCA Civ 420 (03 April 2012) (blogged here) emphasised the centrality of open justice and the rule of law to the common law tradition, and upheld the Guardian’s application for access to court documents opened during a high profile extradition hearing. It would be unfortunate if any access provisions added to the Legal Services Regulation Bill were to cut down on this common law right. However, given that the statutory incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights mean that any legislative restrictions upon the principle of open justice must be read in a manner compatible with Convention rights such as Article 6 (fair trial) and Article 10 (freedom of expression), there would be interpretative limits on any restrictions on open justice added to the Legal Services Regulation Bill. Moreover, the Constitution would place even more substantive limits on such restrictions (in common with other jurisdictions, such as the US, South Africa, and Canada, where the principle of open justice is underpinned by constitutional provisions), so that an overbroad or disproportionate restriction upon the principle of open justice in the Legal Services Regulation legislation would be unconstitutional.

In many ways, therefore, provisions in the Legal Services Regulation Bill providing for access to court documents will simply restate rights that already exist. However, if they encourage the exercise of these rights, then that will be a good day’s work. We might not get courtrooms as packed as in the picture above. However, if court documents are available to the media to explain proceedings to the public (as the Supreme Court explained in Irish Times v Ireland [1998] 1 IR 359, [1998] 2 ILRM 161 (2 April 1998) (doc | pdf)), then that will be a thoroughly good thing for the rule of law and Irish society.

Update 1: following up Dearbhail’s article in yesterday’s Irish Independent, Seth Tillman draws my attention to his op-ed in the same paper: Time to open up courts and let justice be seen. He points out that the High Court of Australia posts the parties’ legal submissions on its website; that in the US, legal submissions are posted on the websites of the two dominant electronic publishers, Westlaw and LexisNexis; and that in Canada, England & Wales, New Zealand, and South Africa, processes are place for the public to request such documents. In his view, there are four compelling arguments why similar materials should be publicly available in Ireland as well:

First, the current position of the Irish courts is inconsistent with modern notions of transparency, access to information, … simple fairness[,] … [and] prevailing western good governance norms. …

Second, these submissions often form the basis of hearings, oral arguments, and other trial court or appellate proceedings. But such proceedings are incomprehensible (or nearly so) without advance access to these documents. …

Third, competition for legal services is stifled by the lack of public access to these documents. … [Lawyers] who wish to practise in a specialty which is new to them lack access to a library of written filings to use as models. Ultimately, this bids up the price for legal services at the expense of overall consumer welfare. …

Fourth, the only way journalists can get copies of legal submissions in advance of a hearing is to ask (actually, beg) … [lawyers] on the case for a copy. … [Such lawyers] can extract favourable coverage from journalists covering public proceedings. … If you want honest newspapers and media coverage, you have to open the courts up.

I am therefore with him that the Legal Services Regulation Bill should institute a reasonably transparent process permitting public access to court documents, such as legal submissions and court transcripts. Time will tell whether this hope will be realised.

Update 2: Two other Irish blawggers have taken up Tillman’s op-ed. First, Paul McMahon on Ex Tempore writes about his frustrations at running a blog about the Irish Supreme Court and seeking to blog about upcoming hearings and decisions without access to the parties’ submissions. And he argues that “regardless of whether access to court documents is protected by the letter of the Constitution, a blanket ban on access violates its spirit”. For the kinds of reasons I explore here, I entirely agree. Second, Rossa McMahon on A Clatter of the Law argues that, since we can’t all access the courts, we should at least have access to court documents:

Tillman is absolutely correct in arguing that the lack of public access to court documents effectively limits public access to the courts and therefore the citizen’s right to see justice being done. In addition, it must obviously make life unnecessarily difficult for journalists who must rely on what is said in court along with whatever information the parties are willing to share. In fact, it is often difficult or impossible to even obtain a copy of a written judgment resulting from court proceedings.

As I have commented before on this blog, Justice may be blind, but the public are not, and they should not lightly have blindness thrust upon them.

What copyrights are attached to court docs in Ireland? In the US the material is public domain with Westlaw etc building their services around ancillary material/indexing/commentary etc. John Boyle has a very approving account of that system in his book the Public Domain.

Given not all documents submitted are by officers/employees state is there any issue there? If someone must submit something in documents over which they have an intellectual property claim they cannot be asked to surrender their property in order to have justice done. Could this happen with a trade secret say? Or photographs etc?

Section 191(1) of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000 (also here) provides: