I first encountered Occam’s Razor in the writings of Peter Birks:

I first encountered Occam’s Razor in the writings of Peter Birks:

‘It is vain to be done with more what can be done with fewer’; or, ‘Entities are not to be multiplied without necessity.’

(Peter Birks An Introduction to the Law of Restitution (OUP, revised ed, 1989) 75, citing Bertrand Russell A History of Western Philosophy (2nd ed, Allen & Unwin, 1961) 462-463).

Birks also wrote that there “is a counter-principle of ‘Occam’s razor’ … that, as you must not have too many entities, so also you cannot do with too few” (ibid, 91). This is inherent in Occam’s Razor itself, of course, especially as formulated in Einstein’s Constraint, that “Everything should be kept as simple as possible, but not simpler” (emphasis added). But the Birks formulation is stronger, since it suggests that, even though there are virtues in shaving away unnecessary entities, not only are there limits to how much may be shaved away, but there are also virtues in adding necessary entities in. Let us call this “Birks’s Augmentation”.

All of this occurred to me as I was reading two interesting cases of restitution for unjust enrichment in which judgment was handed down just before Christmas. They are the opinion of Lord Burrows giving the advice of the Privy Council in Samsoondar v Capital Insurance Company Ltd (Trinidad and Tobago) [2020] UKPC 33 (14 December 2020) (Samsoondar) and the decision of Thornton J in the Queen’s Bench Division in Surrey County Council v NHS Lincolnshire Clinical Commissioning Group [2020] EWHC 3550 (QB) (21 December 2020) (Surrey). I will discuss them and the issues to which they give rise in this post, and in six more posts on this blog (parts II, III, IV, V, VI and VII of this series).

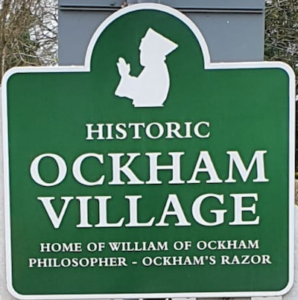

Occam’s Razor is attributed to the fourteenth century English Franciscan Friar and philosopher, William of Ockham, who is believed to have been born in, and is commonly named for, Ockham, a small village in the borough of Guildford, Surrey. [Update] After noticing this post, Steven Elliott QC was passing through the village and spotted this sign (right; click through for larger version): “Historic Ockham village, home of William of Ockham, philosopher – Ockham’s razor”. Thanks, Steven, for taking a photo and sending it on [/update]. It may be this connection that started me ruminating on Occam’s Razor and Birks’s Augmentation in the context of the Samsoondar and Surrey cases. In any event, these two cases are cautionary tales about the application of Occam’s Razor and illustrate that Birks’s Augmentation is sometimes necessary.

Occam’s Razor is attributed to the fourteenth century English Franciscan Friar and philosopher, William of Ockham, who is believed to have been born in, and is commonly named for, Ockham, a small village in the borough of Guildford, Surrey. [Update] After noticing this post, Steven Elliott QC was passing through the village and spotted this sign (right; click through for larger version): “Historic Ockham village, home of William of Ockham, philosopher – Ockham’s razor”. Thanks, Steven, for taking a photo and sending it on [/update]. It may be this connection that started me ruminating on Occam’s Razor and Birks’s Augmentation in the context of the Samsoondar and Surrey cases. In any event, these two cases are cautionary tales about the application of Occam’s Razor and illustrate that Birks’s Augmentation is sometimes necessary.

In Samsoondar, one of Samsoondar’s trucks had been involved in an accident with a third party. Capital Insurance Company Ltd (Capital) subsequently paid $43,400 to the third party, and then sought it back from Samsoondar, on the basis of the insurance contract or as an unjust enrichment. Both claims failed in the Privy Council (Lord Burrows; Lords Lloyd-Jones, Briggs and Leggatt, and Lady Arden, concurring; noted Steve Hedley “Restitution and Car Crashes: A Simple Case of Mistake” (2021) 80(1) Cambridge Law Journal 6). As to the contract claim, legislation had been interpreted by the courts in Trinidad and Tobago as requiring insurance companies in Capital’s position to discharge the liability to the third party, thereby effectively permitting those companies to rely on the insurance contracts to recover from the insured parties; but the Privy Council had reversed this interpretation. As a consequence, Lord Burrows held that the legislation never required Capital to discharge the liability to the third party, and that Capital could not therefore rely on the insurance contract to recover from Samsoondar. The claim to restitution for unjust enrichment failed for similar reasons.

In Surrey, the NHS Lincolnshire Clinical Commissioning Group (Lincs) declined requests by Surrey County Council (Surrey) to assess the eligibility for NHS care of JD, a young man with autism spectrum disorder. As a consequence, pursuant to statute, Surrey were responsible for providing JD with care. In this action, Surrey sought restitution from Lincs for the sums paid by them to a care home for the costs of JD’s care. As a preliminary matter, Thornton J held that, even though the case arose between two public bodies, O’Reilly v Mackman [1983] 2 AC 237, [1983] UKHL 1 (25 November 1983) posed no bar to Surrey pursuing a private law claim to restitution for unjust enrichment (at [84]). And, in the event, she held (at [91]) that Surrey succeeded in a claim for 6 years worth of costs of care, but that claims for earlier costs were statute-barred.

Lord Burrows in Samsoondar (at [18]; following Benedetti v Sawiris [2014] AC 938, [2013] UKSC 50 (17 July 2013) [10] (Lord Clarke; Lords Kerr and Wilson concurring); Revenue and Customs v Investment Trust Companies [2018] AC 275, [2017] UKSC 29 (11 April 2017) [24], [39]-[42] (Lord Reed; Lords Neuberger, Mance, Carnwath and Hodge concurring)) and Thornton J in Surrey (at [9]; following Banque Financière de la Cité v Parc (Battersea) Ltd [1991] 1 AC 221, 227, [1998] UKHL 7 (26 February 1998) (Lord Styen)) both held that, when determining whether the elements of a claim in restitution for unjust enrichment are made out, it is necessary to address four questions:

- Has the defendant been enriched?

- Was the enrichment at the claimant’s expense?

- Was the enrichment unjust?

- Are there any defences?

In Ireland, the same four questions arise from the judgment of Keane J in the Bricklayers’ Hall case ((see Dublin Corporation v Building and Allied Trade Union [1996] 2 IR 468, 483; [1996] 2 ILRM 547, 558, (24 July 1996) [37]-[40] (doc | pdf | html)). These cases raise interesting questions for the law of restitution for unjust enrichment; I will explore those questions in the next several posts; these four enquiries will structure my analysis as I go; and Occam’s Razor and Birks’s Augmentation are both certain to make a few appearances along the way. Our first stop, in my next post, will be to consider whether, in both cases, the defendants were enriched at the plaintiffs’ expense.

7 Reply to “Samsoondar v Capital Insurance and Surrey Co Co v NHS Lincolnshire CCG – Part 1 – Introduction: Occam’s Razor and Birks’s Augmentation”