Cold winds now blow in the US Supreme Court around the stability of a century’s worth of First Amendment doctrine; even New York Times Co v Sullivan 376 US 254 (1964), the most stable of that Court’s speech precedents, now seems in danger of being blown away in the storm, thanks to the recent decision in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v Bruen 597 US __ (2022) (Opinion pdf | Cornell | Justia | SCOTUSblog). In an earlier post on this blog, I considered the potential impact on the First Amendment of Thomas J’s originalist reasoning in the Second Amendment case of New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v Bruen, and found some distinctly chilly zephyrs. Thomas J for the majority (Roberts CJ, and Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett JJ concurring) held that a restriction on carrying arms in public for self-defense reasons was inconsistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearms regulation and was thus unconstitutional. Thomas J explicitly eschewed any standard of review such as strict or intermediate scrutiny, and it was with this that the minority (Breyer J; Sotomayor and Kagan JJ concurring) took most issue. This is nuts. Worse, in Bruen, Thomas J asserted some similarities in analysis between the Second Amendment and the First. In my post on that case, I argued that a similar approach to the First Amendment, and eschewal of tiers of scrutiny in that context, would be even nuttier, but could not be ruled out.

Cold winds now blow in the US Supreme Court around the stability of a century’s worth of First Amendment doctrine; even New York Times Co v Sullivan 376 US 254 (1964), the most stable of that Court’s speech precedents, now seems in danger of being blown away in the storm, thanks to the recent decision in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v Bruen 597 US __ (2022) (Opinion pdf | Cornell | Justia | SCOTUSblog). In an earlier post on this blog, I considered the potential impact on the First Amendment of Thomas J’s originalist reasoning in the Second Amendment case of New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v Bruen, and found some distinctly chilly zephyrs. Thomas J for the majority (Roberts CJ, and Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett JJ concurring) held that a restriction on carrying arms in public for self-defense reasons was inconsistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearms regulation and was thus unconstitutional. Thomas J explicitly eschewed any standard of review such as strict or intermediate scrutiny, and it was with this that the minority (Breyer J; Sotomayor and Kagan JJ concurring) took most issue. This is nuts. Worse, in Bruen, Thomas J asserted some similarities in analysis between the Second Amendment and the First. In my post on that case, I argued that a similar approach to the First Amendment, and eschewal of tiers of scrutiny in that context, would be even nuttier, but could not be ruled out.

Now Matthew Schafer reports that the predictable Bruen assault on the First Amendment has begun: a website creator is using the Second Amendment to try and upend the First:

While Bruen’s equivalency between the First and Second Amendment is provably false, … [the plaintiff’s] resort to it [here] makes sense as a majority of the Court is now on the record in Bruen recasting the Court’s prior First Amendment precedent in two dramatic ways.

First, while the Court has — in general — looked to history to help it understand what speech is protected by the First Amendment, it has nevertheless extended constitutional protections even to speech that has been historically unprotected.

Second, the Court has never held that the proper approach to understanding the scope of First Amendment speech rights in any given case is solely through an analysis of the Amendment’s text, history, and tradition.

Bruen’s gaslighting on both points is a harbinger for changes to come to First Amendment doctrine … Whether the Court’s conservative wing will make good on their dramatic reimagining of the First Amendment in … [this case] remains to be seen. At least two justices — Thomas and Gorsuch — have suggested in other First Amendment cases that history should be the guide. The only question now is whether three other justices will agree.

The case is 303 Creative LLC v Elenis, on appeal from No. 19-1413 (10th Cir. 2021) (also noted on this point here); certiorari was granted on 22 February 2022 (pdf); it has now been set down for argument on Monday, 5 December 2022 (pdf); and updates can be monitored via SCOTUSblog.

It is not the only context in which Bruen could undermine the First Amendment. Chad Flanders “Flag Bruen-ing

It is not the only context in which Bruen could undermine the First Amendment. Chad Flanders “Flag Bruen-ing

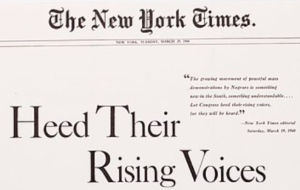

Texas v Johnson in Light of The Supreme Court’s 2021-22 Term” 2022 University of Illinois Law Review Online 94 considers whether the Supreme Court’s First Amendment protections for flag burning as a form of political process could survive Bruen, and fears that they may not. But the main target is New York Times Co v Sullivan 376 US 254 (1964). Whatever about Thomas J’s views about the First Amendment in general, he has recently become a persistent critic of the strong First Amendment protections afforded in particular in that case. The Supreme Court unanimously held that, under the First Amendment, to maintain a claim for defamation, a public official must prove that the defendant acted with “actual malice”: that is, the defendant made the statement with with knowledge of its falsity or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not. Brennan J wrote the opinion of the Court, in which Warren CJ, and Clark, Harlan, Stewart and White JJ joined; Black J wrote a short concurring opinion; Goldberg J concurred in the result; and Douglas J concurred with both Black and Goldberg JJ. An action by LB Sullivan (pictured here), an elected Commissioner of the City of Montgomery, Alabama, against the New York Times, for defamation in an advertisement placed by the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South (element, above right), therefore failed. In Hustler Magazine, Inc v Falwell 485 US 46 (1988) (Cornell | Justia), Sullivan‘s actual malice standard was unanimously approved, and applied to the context of the tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress. And this in turn was approved 8-1 in Snyder v Phelps 562 US 443 (2011) (Opinion pdf | Cornell html | Justia | SCOTUSblog). Update: as for more general critiques, see David McGowan “A Bipartisan Case Against New York Times v Sulliavan‘ (2022) 1(2) Journal of Free Speech Law 510 (pdf); Carson Holloway Rethinking Libel, Defamation, and Press Accountability (Claremont Provocations Monograph Series; 2022).

Although he joined the opinion of the Court in Snyder v Phelps without comment, Thomas J has recently found his voice on this issue, and it is a critical one. For example, in McKee v Cosby 586 US __ (2019) (pdf) (concurring in denial of certiorari), he wrote that the constitutional libel rules adopted in Sullivan “broke sharply” from the common law, that there are sound reasons to question whether the First Amendment “displaced this body of common law”, and that Sullivan‘s actual malice standard bears “no relation to the text, history, or structure of the Constitution”. Taking up this point, in Tah v Global Witness Publishing, Inc 991 F3d 231 (DC Cir, 2021), Silberman J (dissenting in part) called for Sullivan to be overruled, on the grounds that its “holding has no relation to the text, history, or structure of the Constitution, and it baldly constitutionalized an area of law refined over centuries of common law adjudication” (id, 251). Certiorari was denied on 1 November 2021 (Order List (pdf) p3), without comment from Thomas J. However he reiterated his anti-Sullivan sentiments in Berisha v Lawson 594 US __ (2021) (pdf) (dissenting from denial of certiorari) and Coral Ridge Ministries Media, Inc v Southern Poverty Law Center 597 US __ (2022) (pdf) (same)), and called for the Court to reconsider Sullivan. Gorsuch J also dissented for the same reasons in Berisha (ibid); Kagan J called Sullivan into question before she went on the bench (whilst the late Scalia J was no fan of it either). Alito J dissented in Synder v Phelps because, although Sullivan permits expression that is “uninhibited”, “vehement”, and “caustic”, it does not permit the intentional infliction of severe emotional injury on private persons at a time of intense emotional sensitivity by launching vicious verbal attacks that make no contribution to public debate.

On the one hand, the argument for the fragility of Sullivan after Bruen is examined in Alexander Hiland & Michael L Smith “Using Bruen to Overturn New York Times v Sullivan” 50 Pepperdine Law Review (forthcoming) (SSRN). On the other hand, Schafer has been constructing defences against these assaults on Sullivan; eg, blog: here, here, here, here, here, and here (also here and here); and see “In Defense: New York Times v Sullivan” 82(1) Louisiana Law Review 81 (2022) and Matthew Schafer & Jeff Kosseff “Protecting Free Speech in a Post-Sullivan World” (2022) Federal Communications Law Journal (SSRN).

In Club Madonna Inc v City of Miami Beach __ F 4th __ (11th Cir; 1 August 2022), Newsom J (concurring) argued that First Amendment doctrine has too many standards, tests, and factors, and called for a “return to first principles”. 303 Creative may do precisely that, and may even undermine the First Amendment’s tiers of scrutiny in the process, though it need not address Sullivan. If it does not, then Donald Trump may already have commenced a vehicle in which the Supreme Court could complete the job. Trump has a long-standing animus against Sullivan; and his latest defamation claim against CNN may very well be the case in which any application of Bruen to the First Amendment in 303 Creative‘s embrace of Bruen could in turn be applied in the context of Sullivan. Given that the nutty wing of the Originalist camp now in the SCOTUS ascendency had no problem in reversing one landmark precedent (when they overruled Roe v Wade 410 US 113 (1973) in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization 597 US __ (2022) (Opinion pdf | Cornell | Justia | SCOTUSblog)), they will doubtless have little compunction in doing so again if they decided that Sullivan too was egregiously wrong, without grounding in the constitution, and unworkable. If that were to come to pass, then Winter would truly have come for the First Amendment.

One Reply to “Winter is coming: the future of First Amendment analysis, and the prospects for New York Times v Sullivan, after NYSR&PA v Bruen”